Container companies buy into other parts of the supply chain, including warehousing and distribution

The wonders — and absurdities — of globalisation were thrust into the spotlight last month when a ship built in Japan, insured in the UK, flying a Panamanian flag and manned by an Indian crew wedged itself across one of the world’s busiest waterways, adding further strain to supply chains that have been tested to the limit during the pandemic.

Yet global trade, though disrupted, did not grind to a halt. Instead, vessels that ordinarily would have passed through the Suez Canal were mostly rerouted around the Cape of Good Hope. Once the canal reopened, relieving the backlog took less than a week.

The episode may have led to delays, “but overall its effects were negligible”, says Jan Hoffmann, chief of trade and logistics at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

“It’s not as though people were unprepared for a Suez-like incident,” he notes. “Companies already knew not to depend too much on one route or supplier.”

Nevertheless, Soren Skou, chief executive of AP Moller-Maersk, the world’s largest container shipping line, said last week that the blockage would encourage companies to diversify their suppliers, bulk up inventories and rely less on “just in time” strategies.

Graham Slack, the group’s chief economist, agrees that it is “remarkable” how supply chains had held up over the past 12 months, but adds that shipping executives must soon decide whether “black swan” events are “one-in-100-year or one-in-20-year” phenomena and adapt their strategies accordingly.

Or, as Shehrina Kamal, product director at supply chain risk consultancy Everstream Analytics, puts it: “Today is the Suez Canal, yesterday was the pandemic and tomorrow is hurricanes.”

In a survey of supply chain executives conducted in May, McKinsey, a consultancy, found that 93 per cent planned to beef up the resilience of their supply chains, either by building in redundancy across suppliers, reducing the number of unique parts in products or regionalising their business.

Any pandemic-induced reshoring of supply chains would be a blow for the container shipping industry, which reported huge profits last year despite the chaos unleashed by Covid-19. But many in the industry remain sceptical of talk of localisation or shifts from just-in-time to just-in-case supply chains, more generally.

Peter Sand, chief shipping analyst at Bimco, an association of ship owners, doubts there will be major changes to the ways companies source their parts.

In fact, “the pendulum has swung back in favour of established supply chains”, he suggests, as western companies have noticed how China has handled the pandemic relatively well.

“When companies lack the parts they need, it’s normal to think ‘why are we doing things this way’, but at the end of the day the alternatives aren’t there,” he explains. “It’s hard for most players to move away from their reliance on China.”

Hoffmann also concludes that “diversification [of suppliers] is more likely than reshoring”.

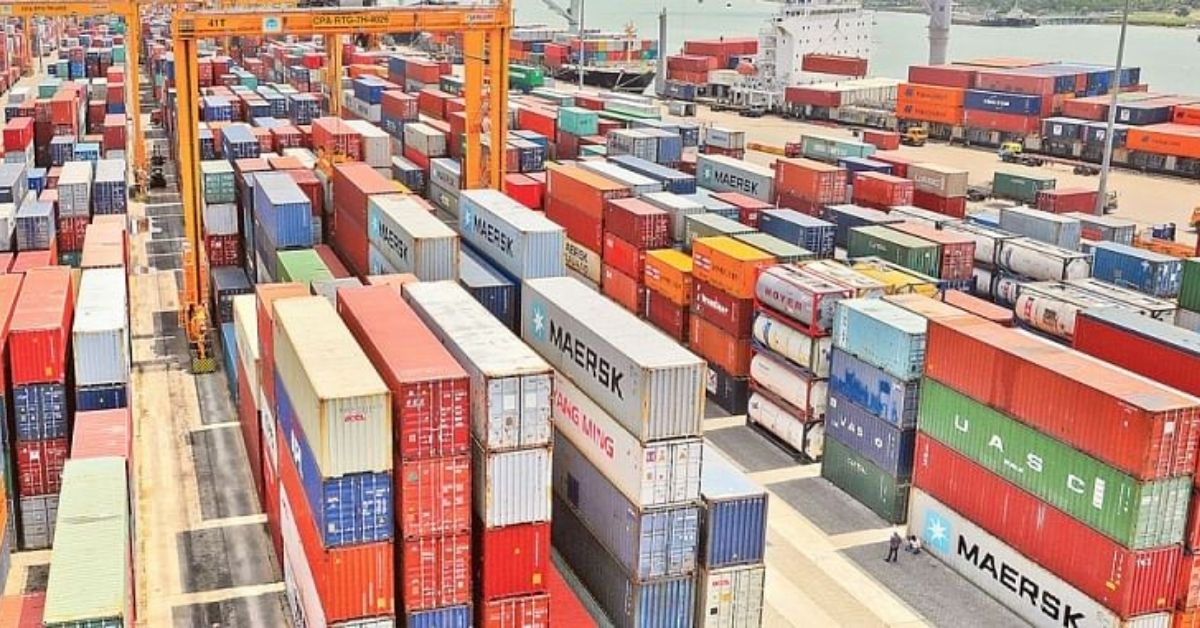

Some of the biggest container shipping companies have spent much of the past year on their own diversification: acquiring other supply chain actors, such as freight forwarders and warehouse operators.

“Carriers already looked at the rest of the supply chain with quite some envy,” says Alan Murphy, founder of Sea-Intelligence, a consultancy.

Hapag-Lloyd, the world’s fifth-largest container line by capacity, last month absorbed NileDutch, a provider of container services to and from west Africa. French carrier CMA CGM last month purchased four Airbus aircraft that will fly between Europe and North America to offer “agile solutions” to its customers.

Maersk’s purchase of US-based warehousing and distribution group Performance Team and KGH Customs Services was also finalised last year, which it says is contributing to the “general upgrade and improvement” of its logistics and services business — a unit that last year more than doubled its earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation to $470m.

Rising demand for ecommerce — likely to be given a further boost by US President Joe Biden’s recent $1.9tn stimulus package — was almost certainly a factor behind Maersk’s move into warehousing, says Sand. Carriers “can see the likes of Amazon making bucketloads of money while having their goods shipped cheaply”.

“If [carriers] can add warehouses and freight forwarding to their business, that gives them an edge,” he says. “But many have tried in the past and failed miserably.